As a creator of interactive media, I don’t fit easily into a single silo, having worked on projects from mixed reality military simulators to action figure-based board games. So it should come as no surprise that my most frequently asked question is “so just what is it that you do?”

As is often the case, the short answer is not necessarily the best answer.

My catch-all answer of “I’m a producer” usually draws crinkled brows and polite nods, as that role is defined in vastly different ways across industries and even varies from studio to studio. Indeed, my own roles vary from project to project (and over the life of a project), encompassing that of executive producer, product manager, and designer, all rolled into one.

When expanding on what the means, I’ve been told my elevator pitch would work only on the Burj Khalifa.

So perhaps a more meaningful answer is I assess and meet people’s needs. This is applied differently in the various roles I take, but the core skills are the same: a willingness to listen, a desire to learn, and an ability to put it all together.

Willingness to Listen

Many people think they’re good listeners, just like many people think they’re good drivers – it’s everyone else who is the problem.

The temptation for anyone in a creative role – particularly when consulting – is to quickly demonstrate just how smart and clever you are to your client. High expectations and short timelines put tremendous pressure on you to launch into a solution before you understand the problem.

As executive producer, an inability or unwillingness to genuinely listen to your client’s story and needs can critically damage the trust they have in you. Your willingness to actively listen demonstrates respect for both them and their circumstances, and is critical for laying the foundations of a successful project: understanding, trust, and cooperation.

As product manager, acting without first really listening to can result in wasted time and effort as you focus on the wrong priorities and demonstrate a lack of empathy for your audience. This in turn affects the work of a designer, as every action or interaction should serve the needs of the audience and the goals of the product as a whole.

Even on a personal level, we appreciate feeling heard. Who likes having someone else tell you how you feel or how you should solve your problem without first having really listened to you?

I was in a roundtable discussion with clients who were very bright, non-technical academics. They wanted a simulation that would reinforce some of the lessons taught to the professionals attending the program. My well-intentioned colleagues, eager to demonstrate their enthusiasm for the client and project, launched into a very interesting and detailed description about just what the simulation should be and how it would work. It was a cool idea and pretty impressive-sounding, really. And it was all terribly wrong for the client.

I could see the clients’ expressions around the table – people who knew they were listening to an expert provide an expert solution, but it was a solution that didn’t feel right in ways they couldn’t articulate. Putting on the brakes, asking open-ended questions, and providing space for the clients to put things in their own terms got us back on track to really understanding their circumstances and problems, and built trust that we could ultimately deliver the experience their alumni needed.

Investing the time to listen doesn’t preclude “moving fast and breaking things,” but it pays to know what you’re breaking and why.

As an expert in my field, yes, my gut instinct might be completely correct, but a little humility and willingness to listen to others pays off no matter what I’m working on.

Desire to Learn

Coupled with a willingness to listen is a desire to learn. Creating impactful products and experiences requires an understanding of markets, people, and domain knowledge. This can take many shapes: performing product comparisons, consuming source material, working with subject matter experts, developing user persona and/or empathy maps, and so on.

It’s more than compiling data, however. It’s immersing myself in the knowledge and striving to become an “expert” in a new field, or at least have a functional understanding that enables you to speak to the needs of your client and audience. For that, you really need to enjoy learning and experiencing new things, embracing both the growth (and occasional discomfort) that brings.

Sometimes it’s about really getting into the shoes – or boots – of your audience. I was asked to create a game-based learning simulation for the US Army to teach the planning and decision making around logistics. To better understand the experience of the Soldiers I’d be serving, I travelled to Fort Hood, Texas, and took the same week-long crash course the troops take. A similar opportunity took me to the deserts of the National Training Center and a ride with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment. In both instances, I was able to learn things that aren’t captured effectively in typical user research. Like how sand gets everywhere, including your teeth.

Ability to Apply

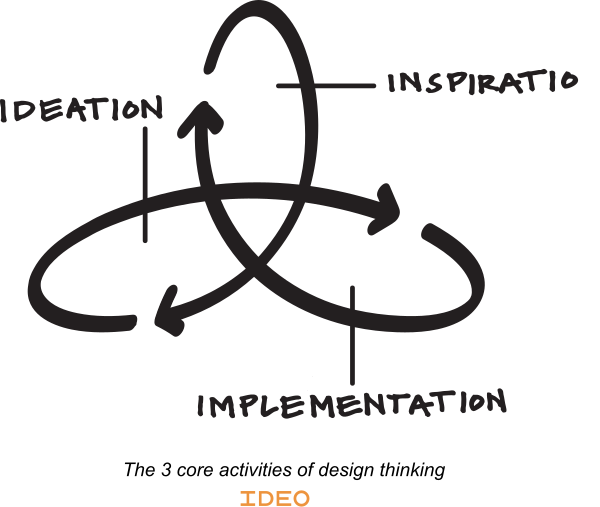

All of the above is well-intentioned but ultimately meaningless without the ability to apply it to solve problems effectively. This requires not only the capacity to synthesize what you’ve heard and learned, but the unwavering focus on the client’s and audience’s needs, as well as the discipline to continually revisit your efforts to make sure they remain on target.

As executive producer, that means establishing a common vocabulary with your client and maintaining clear, honest communication with them throughout the life of a project.

As product manager or designer, that involves continually reevaluating your work, making sure that even as you adapt to newfound learning and changes in the market or simply come up with cool ideas, your plans and design remain focused on fulfilling the real needs you’ve assessed.

Without discipline, this can be a haphazard or reactionary exercise, chasing after an ever-changing goal. Staying focused on what I’ve listened to and learned makes this iterative process one of continual refinement and improvement, better serving the needs of my client and audience.

That’s how I strive to serve people both personally and professionally, assessing, understanding, and meeting their needs, because ultimately helping them achieve success is my success as well.

Ah. We’ve reached the top floor. I hope you enjoy the view.