Project leadership lessons from Napoleon’s last campaign

The anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte‘s final defeat at Waterloo is a good opportunity to look at his last campaign and see what lessons about project leadership we can learn.

Some brief (no, really) historical context:

In 1815, Napoleon escaped from exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba and returned to France, quickly rebuilding his government and army. The European monarchies swiftly formed a new coalition and declared war on him. Personally. (As an aside, you have to take it as a compliment when nations don’t just declare war on your country, they declare war on you.)

Napoleon was facing a war with pretty much everyone from Britain to Russia, and a pretty shaky political situation at home. The immediate threat, however, was the Anglo-Dutch (that’s British, Dutch, and Belgians) army under the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian (think German) army under Marshal Blucher, both assembling in nearby Belgium.

Napoleon faced them with an experienced, motivated team of highly professional “industry veterans.” So how did he lose?

Setting a bold vision…

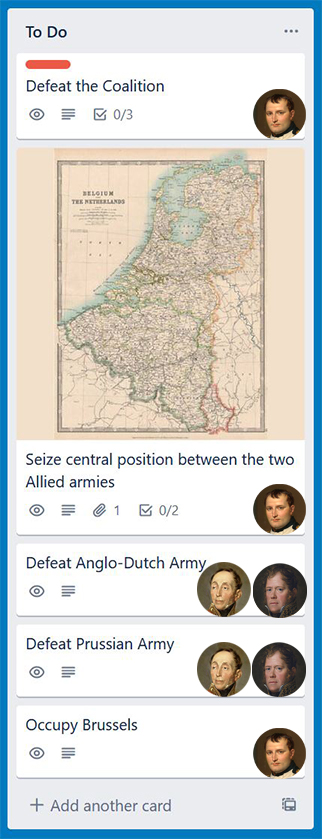

Napoleon needed a quick win to both quiet his political opponents in Paris as well as prevent a combined Anglo-Dutch-Austrian-Italian-Prussian-Russian-pretty-much-everyone-else Allied army from crashing his party all at once. To do that, he set out on a daring plan: to get between the Anglo-Dutch and Prussian armies. He would keep one opponent busy while he defeated the other, then turn to wreck the former.

Napoleon didn’t specify which army he intended to defeat first. Instead, he established the goals and remained flexible about the interim steps to achieving them.

It was risky—he could be trapped between the two enemy armies and destroyed—but it was bold, unexpected, and served clear goals. That’s a good model for any leader, setting an ambitious, inspiring vision and outlining the tasks that will lead toward making it a reality.

It started well. On June 15, 1815, Napoleon crossed into Belgium at the head of his Armee du Nord and got between the Anglo-Dutch and Prussian armies, just as he planned. The Duke of Wellington, who was attending a ball when he received the news, reportedly exclaimed “Napoleon has humbugged me, by God!”

Great start! And then things started to go terribly wrong.

…but failing to communicate it

Napoleon had successfully set tasks, but his subordinates didn’t necessarily understand the real vision.

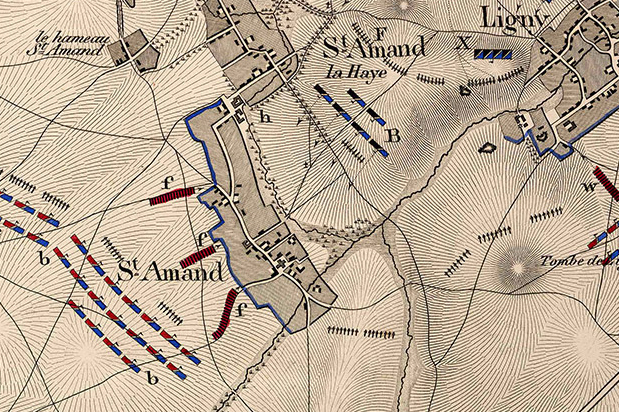

On June 16, Napoleon’s army fought two battles simultaneously, one against the Anglo-Dutch at the crossroads of Quatre Bras, and one against the Prussians at Ligny. Napoleon had given Marshal Michel Ney a big chunk of the army to hold off the Anglo-Dutch while Napoleon himself would defeat the Prussians.

During this double battle, the confusion of specific tasks with long-term goals and vision would prove disastrous for Napoleon.

Comte D’Erlon’s French corps was heading to support Marshal Ney in holding back the Anglo-Dutch at Quatres Bras. Napoleon realized that D’Erlon’s men would be perfectly placed to march down the road and attack the Prussians from the rear. That would shatter the Prussians and then allow Napoleon to turn and defeat the Anglo-Dutch. He sent orders for D’Erlon to come to Ligny.

Marshal Ney, facing off against the Anglo-Dutch, had started the day well but was having more trouble the longer the battle went on. He had come close to defeating the Duke of Wellington early, but now lost sight of his goal of distracting one enemy while the other was being beaten. Instead, he looked for more troops to renew the fight: D’Erlon’s.

What are you working for?

D’Erlon, not really understanding his part in either battle, responded to the call from Napoleon’s courier and turned for Ligny. His orders were not clear, only the urgency, so D’Erlon marched straight for Napoleon, not toward the rear of the Prussians. This caused quite a stir when his troops were initially mistaken for Prussians sneaking up on the French. That made Napoleon delay his attack on the Prussians for a crucial period.

(It didn’t help that he was told to march by way of “St. Amand” and there are different roads leading to no less than three St. Amands in the area.)

Things got worse when Ney, learning that Comte D’Erlon’s corps was marching off in the “wrong” direction, sent orders for him to march back to the battle at Quatre Bras. Poor D’Erlon, caught between two conflicting tasks, went with the orders of his immediate superior, Ney. He left the battle at Ligny too early to have an impact, and then arrived at Quatre Bras too late to have an impact. Being present at either fight might have been decisive.

This is where goals are more important than tasks. Tasks–the actual work of any project–must always be in support of the project goals, otherwise it’s wasted effort.

Now, we live in a time when our projects are (usually) not relying on couriers and handwritten messages, but miscommunication and misunderstandings still abound.

How many different ways is your team communicating? Verbally? Slack? Email? Texts? Who is responsible for managing those?

Napoleon’s team leaders, operating under significant time pressure, relied on written and verbal instructions, not always entirely clear on the relative importance of each.

How many “commanders” do the people on your team answer to and what do they do when there’s a conflict? How many different ways are your goals being communicated?

Project/company goals need to be communicated clearly to everyone. All team members are decision makers on some level, so all team members need to fully understand goals (why you’re doing what you’re doing) not just their specific tasks (how you’re doing what you’re doing).

Project resources should be directed at core objectives not “cool ideas” or even “new opportunities” unless those opportunities serve the real objectives. Agile development doesn’t mean chasing the new (or worse, avoiding making decisions), it means adapting to best achieve objectives. Leaders need to clearly communicate objectives—“why”—so that the “how” of project development can adapt to circumstances without losing sight of the objective.

How do you know everyone understands your goals?

One way is to share those goals in the medium that works best for your team. That may mean sharing the project vision in multiple formats, such as verbally, visually/graphically, etc. Communicating ideas to your team in different styles can not only increase their understanding of the goals, the process of formulating those ideas helps you better refine and sharpen them.

Another way to make sure everyone understands the goals is to not be the only person communicating them. While it can be important to have a “keeper of the vision” on a project, it’s vital that anyone could step into that role if “the keeper” is unavailable.

A practical step you can take is letting other people explain your goals in their own words. Memorization does not necessarily mean comprehension, and having people merely parrot back what you’ve said doesn’t show understanding. Instead, listen to your team leads explain project goals to their teams in their own words to get a sense of their actual understanding and ownership.

Establishing a consistent vision let’s everyone on your team know what you’re wanting to achieve and how, even if you haven’t discussed the specifics of a given task. When I was lead designer at Pandemic Studios, co-founder Josh Resnick was always consistent in his goals and expectations. Whenever I was purchasing equipment or resources, I could ask myself “What would Josh do?” and act accordingly without the need to wait for specific approval.

If your team doesn’t really understand the project goals or your ultimate vision, they’ll be like D’Erlon’s poor troops marching back and forth on their tasks, ultimately accomplishing nothing.

Owning your decisions

Two days after nearly pulling off a double win with the simultaneous battles at Ligny and Quatres Bras, Napoleon was defeated when the Anglo-Dutch and Prussian armies pulled themselves together at Waterloo.

Soon after, Napoleon was forced once more to abdicate, this time going into exile in the South Atlantic. He spent his last years brooding on the failure, often very critical of his subordinates’ actions (or inactions) in that critical three-day span.

Napoleon complained bitterly about his team’s mistakes and his ‘hiring decisions’ that put those people in position to fail him.

“I should have destroyed [the enemy] at Ligny, if my left had done its duty. I should have destroyed him again at Waterloo if my right had not failed me.”

“Had it not been for the imbecility of Grouchy, I should have gained the day.”

“I made a great mistake in employing Ney… I ought not to have employed Vandamme.”

Napoleon blamed Ney for failing to destroy the Anglo-Dutch at Quatre Bras, but it was Napoleon who intended Ney to delay the enemy while Napoleon defeated the Prussians.

Ney was also blamed for taking D’Erlon’s men away at a crucial time, but it was Napoleon who failed to communicate to Ney what his goal really was, not just the tasks assigned.

Napoleon complained about trusting Ney and others, but these were all experienced, accomplished leaders. (And it was Napoleon who chose to wait until the morning of the battle at Quatres Bras to put Ney in command.)

Did Napoleon’s generals make mistakes? Certainly. Did those mistakes cost him the campaign? Possibly.

But who was really responsible for those mistakes?

Failure–and the responsibility for it–ultimately begins and ends at the top.

Project leadership is not a title or role, it’s a continual, active process. Leaders not only establish the vision and goals of a project, but they must make sure that everyone on the team understands that vision and is taking steps toward fulfilling it.

You can’t–and shouldn’t–weigh in on every decision on every task your team is working on. Equipping the people on your team to make the right decisions is part of good leadership.

So what leadership lessons can we take from Napoleon’s last campaign?

- Establish the bold vision

- Ensure the team understands the goal

- Set and adapt tasks to achieve the goal

- …and make sure the Prussians are really retreating!

(This last one may not apply to your project.)

What historical leaders and events inspire your leadership style? Connect with me on Twitter and share your thoughts!

Stay in touch with my newsletter. No spam!

If you like what you read, please share it with others via the links below.