Despite some great leaps forward in hardware usability, virtual reality has struggled to find mass market acceptance. Oculus, HTC Vive, and PlayStation VR sales are respectable but are still fringe items, even in the video game space. There hasn’t been a must-have game nor “killer app” that’s motivated large numbers of casual consumers to invest in VR gear.

I think part of this underwhelming consumer response stems from the isolating nature of current virtual reality experiences. Putting on a headset shuts you off from the world — and people — around you.

Humans are social creatures: we live and thrive in community. For VR to really break out, it must both overcome that isolation and enable social experiences not otherwise possible.

That’s a big ask, as VR requires hardware that’s currently both expensive and cumbersome. Moreover, today’s VR experiences are a poor imitation of normal interaction. This could be changing, however.

Facebook’s Codec Avatar research may be the tool that enables truly social VR — and much more — just by facilitating a good conversation. Codec Avatar uses machine learning and facial mapping to create photorealistic, responsive digital representations of people.

Now, this technology — which currently requires a studio with a massive camera array — isn’t ready for prime time. But as their research matures, Facebook is ideally positioned to capitalize on it.

Where We’ve Been

Video games and other shared interests have inspired the creation of social groups who may have never met face to face. People from geographically distant (or isolated) areas have the chance to form bonds with other players from around the globe.

The tools for this interaction, however, are both limited and awkward. Text is still the primary means of communication, principally by in-app chat messages. If you’ve ever had a hard time catching the nuances of someone’s email or ever had someone misunderstand your text message, you can imagine how limiting in-game chat is.

This may be perfectly adequate for short messages while playing games, but carrying on a sensitive or heart-felt conversation? Not so much.

Many online social groups have turned to voice chat providers like Discord to circumvent the inherent limitations of text chat. Voice offers real-time communication and, more importantly, tone and inflection. This communicates mood, intent, and other information that text alone can’t.

But a disembodied voice still leaves much to be desired. My words and tone may say one thing, but my body language may say something entirely different.

Video chat services such as Skype and Zoom offer real-time face to face interaction, enabling richer verbal and non-verbal communication. While great in many situations, not everyone is — or should be — comfortable revealing their actual identity in an online chat. Although online anonymity offers opportunities for some really bad behavior, there’s a degree of desirable anonymity that is hard to achieve without compromising how we communicate.

Where We Are

Current virtual reality offers a partial solution for this, through the adoption of avatars. These virtual constructs allow for both anonymity and personalization to whatever degree the user desires.

Both Rec Room and Facebook’s Spaces are attempts to create VR social interaction platforms. These aren’t games, but rather environments for people to gather virtually and talk, play, or otherwise socialize.

As you can in the images above, both platforms use very similar avatars to represent people. The simple, stylized look is not just a cute artistic choice, but a deliberate concession to how technology can’t currently emulate some really important aspects of human interaction.

I had the opportunity for a behind-the-scenes chat with folks from Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. These masterful puppeteering engineers talked a lot about the importance of very subtle movements — facial microexpressions. These muscle tics, eyebrow flashes, and other tiny (often unconscious) gestures often go unnoticed by our conscious minds, but are expected nonetheless.

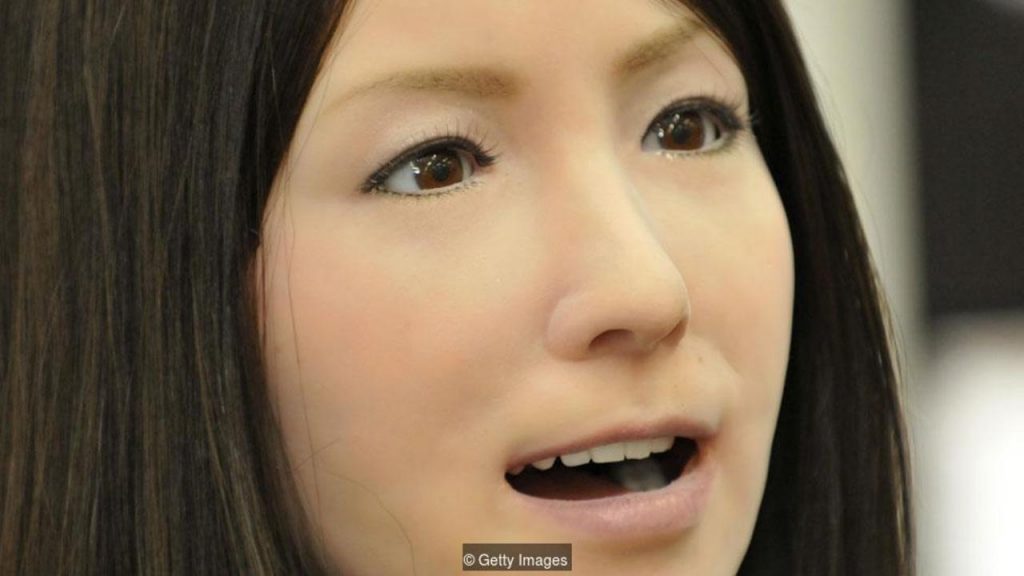

Their absence is immediately noticeable and, frequently, unsettling. Masahiro Mori refers to this as “the uncanny valley.” He suggests humans have a growing degree of affinity to a human-like thing (a robot, for example, or digital avatar) the more realistically human it looks…to a point. Then we’re revolted by it.

In striving to avoid the uncanny valley, the avatars of Rec Room and Spaces are, in turn, too simplistic of communicate the facial microexpressions and other non-verbal cues we need for a natural conversation. Fine for casual game chat, but you aren’t going to do business with that robot zombie above, let alone pour out your heart to her. *shudder*

Where We’re Going

This is where Facebook may save social VR from itself.

The capture of (many) facial microexpressions and real-time responsiveness makes these Codec Avatars incredibly lifelike without causing revulsion. This will enable real-time virtual communications approaching the level of in-person conversations.

This is a sample Facebook Reality Labs released in 2019:

The potential this represents elevates VR to a viable — possibly even preferable — means of long-distance communication for personal and enterprise use.

Instead of tying yourself to a phone (or even Skype or FaceTime screen), your conversation could take place just as comfortably in virtual Tahiti or on Mars without compromising the quality of the verbal and non-verbal interaction.

As VR moves to untethered experiences, it becomes easy to incorporate this as part of a full-body avatar as well. As someone who talks with my hands and likes to walk around while I chat, this is a big plus for me.

Facial microexpressions aren’t restricted to our virtual doppelganger, either. Those movements could be mapped to your favorite avatars, too. You can still be an elf or bunny online when you like, but with all the lifelike expression we expect in a conversation.

The same machine learning data mapping facial microexpressions may offer additional enhancements not possible in normal face to face conversations as well.

Facial microexpression data and natural language processing could be incorporated into a “Social AI.” This could analyze both the verbal and non-verbal conversation data to assess meaning and intent. A virtual overlay associated with a speaker would provide listeners with aid understanding the speaker’s social and emotional cues.

Social AI could potentially offer real-time suggestions on how to respond to or interact with other people. Some researchers are already experimenting with virtual reality and augmented reality to aid people with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Imagine the benefit of having culturally-appropriate tips or prompts available for the international traveler. This could be broadened significantly to facilitate counseling, negotiations, or even awkward first dates. Real-time social coaching, anyone?

I can see Facebook developing a VR/AR headset that captures your expressions in real-time to whatever avatar you can imagine. Combining their Oculus hardware experience, facial microexpression machine learning, and vast social network reach, Facebook is ideally positioned to move consumer VR from the fringes of gaming to the center of social interaction.

Let’s continue this discussion. Connect with me on Twitter and share your thoughts!

Stay in touch with my newsletter. No more than once a week, no spam.

If you like what you read, please share it with others via the links below.